Introduction

Tibet Action Institute presents this Resource Guide for Decolonizing Reporting on Tibet as a tool for journalists, editors, researchers, policymakers, students, and others seeking to report on Tibet with accuracy, integrity, and respect for Tibetan voices.

For more than seven decades, Tibet has been under Chinese occupation, and throughout this time, the Chinese government has sought not only to control life inside Tibet but also to shape how the world understands Tibet’s history and culture.

International coverage of Tibet has too often repeated narratives promoted by Chinese state propaganda—erasing or sidelining Tibetan perspectives, normalizing colonial terminology, and distorting the reality of Tibetan agency and resistance. This guide is designed to directly counter those narratives and equip media professionals and researchers with resources to decolonize their language, center Tibetan perspectives, and represent Tibet and Tibetans on our own terms.

After China’s invasion of Tibet in 1949, our recent history is one of courageous, sustained, and often brutally suppressed resistance to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) occupation. From large scale protests in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, in 1987, 1988, and 1989, to a wave of smaller protests often led by nuns and monks that took place sporadically throughout the 1990s, Tibetans have consistently demanded freedom, dignity, and the return of the Dalai Lama. In March 2008, Tibetans across Tibet, from all walks of life, used the spotlight of the Beijing Olympic Games to launch a nationwide uprising, which was violently suppressed by the CCP, determined to prevent any disruption to its international showcase.. The brutal repression meant that Tibet was sealed off from the outside world: foreign media and diplomats were banned, internet and communications cut, protestors arrested and disappeared, and heavy surveillance was imposed. Many of these restrictions remain in place to this day.

Since 2009, over 150 Tibetans have carried out self-immolation protests. Since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, the situation has only worsened. Under Xi’s rule, the policies of Sinicization and forced assimilation have intensified and accelerated so that the Tibetan language, religion, and culture is absorbed into the larger Chinese narrative. Approximately one million Tibetan students beginning as young as four years old have been separated from their families and required to attend colonial boarding schools, where they are taught in Chinese and cut off from their families, language, and culture.

In addition to a repressive environment, China’s information warfare seeks to erase Tibet as a distinct nation while also impeding the Tibet movement in the international arena. Censorship, state propaganda, and targeted disinformation campaigns aim to discredit the movement and replace Tibetan narratives with those of the Chinese state. Tellingly, Tibet is consistently ranked among the least free countries in the world by Freedom House, receiving the number one ranking in 2025.

This media resource guide is grounded in the belief that Tibetans are the most authoritative narrators of our own history, identity, and lived experience. It provides a database on Tibetan experts, privileging Tibetan voices and Tibetan sources of knowledge while rejecting the normalization of Sinicized names, place names, and terminology. By centering Tibetan names and the correct renderings into Latin script, this guide offers a simple but vital act of resistance against the erasure of Tibet in international reporting.

In addition, we present free-to-use graphics and maps (with attribution to Tibet Action Institute) that reflect the political and physical geography of Tibet, practical suggestions on transliterations, and a curated reading list on contemporary Tibet.

Quick Takeaways Table

| Chinese Government Terminology | Terminology Centering Tibet and Tibetans |

| Xizang | Tibet |

| China’s Tibet | Tibet |

| Tibetan Region | Tibet |

| Western China | Tibet |

| Sichuan Province | Kham / Amdo |

| Qinghai Province | Amdo / Kham |

| Yunnan Province | Kham |

| Gansu Province | Amdo |

| Tibet Autonomous Region | Central Tibet or Ü-Tsang |

| Ethnic Tibetan | Tibetan |

| Ethnic minority | Tibetan people |

| Living Buddha | Rinpoche / Lama |

| 1959 Failed Uprising | March 1959 Uprising against China’s occupying forces that led to the escape of the Dalai Lama into exile, which was then was brutally suppressed |

| 2008 Riots | 2008 Protests |

| Suicide | Self-Immolation Protest |

| Diaspora | Exile |

| Remote/small region | Tibet, a country the size of western Europe |

| Obscure/rare Tibetan language | Tibetan, a rich language with a long history used by millions of people and Tibetan Buddhists |

Geography

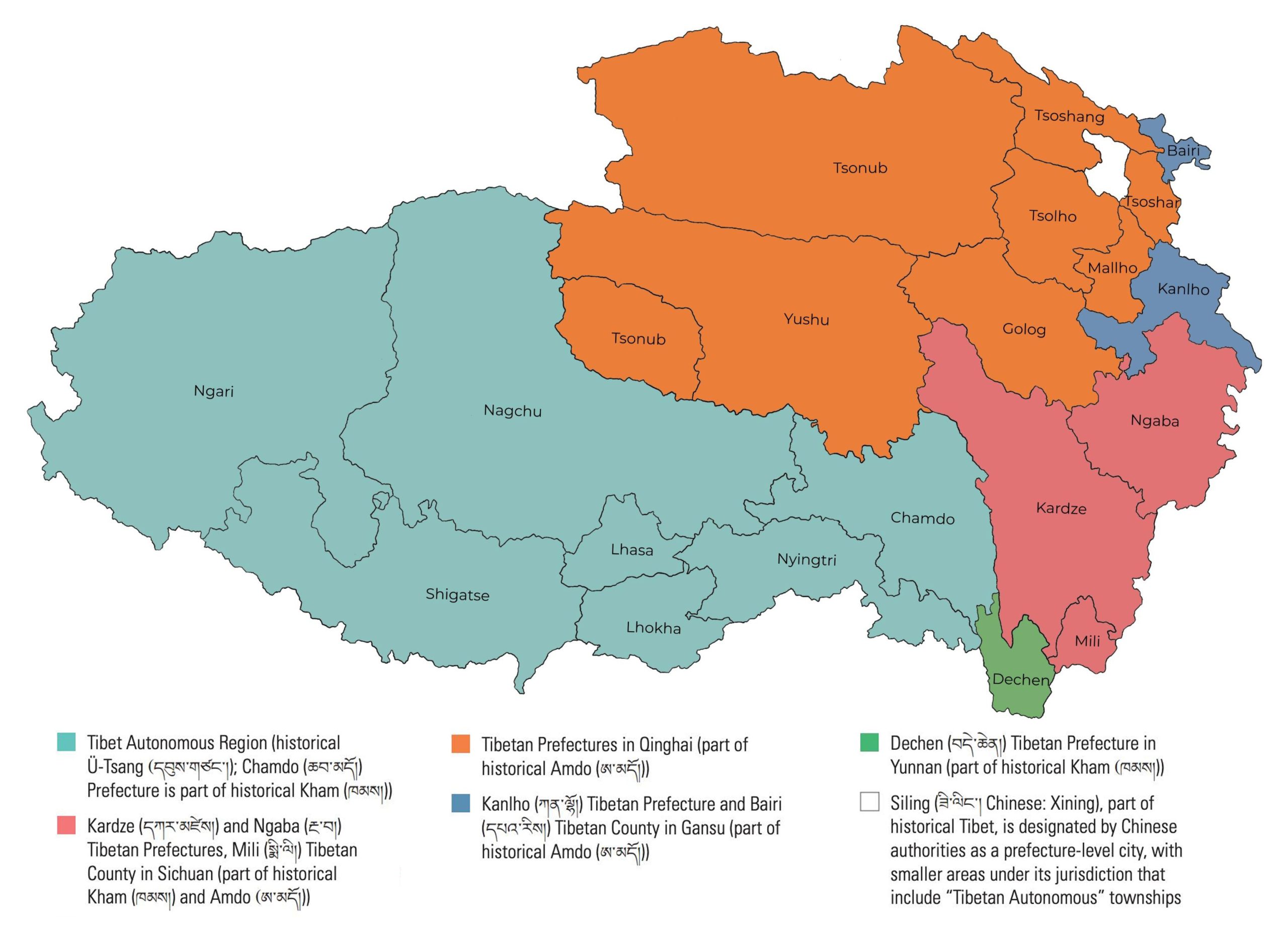

The Chinese government has for decades been attempting to diminish and obscure the existence of Tibet and Tibetans. Historical Tibet is composed of the three provinces of Amdo (ཨ་མདོོ།), Kham (ཁམས།), and Ü-Tsang (དབུས་གཙང་།), home to a common cultural, linguistic, religious, and political heritage. In the 1960s, as part of a broader colonial strategy to undermine Tibetan national identity and suppress potential resistance, the Chinese government dismantled this unified Tibetan territory. It split Tibet into new administrative divisions: the so-called Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) and a patchwork of Tibetan autonomous prefectures (TAPs) and counties within the Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan.

This administrative reorganization was a deliberate political tactic designed to facilitate control over Tibetans and advance a colonial narrative that framed Tibetans not as the majority in their own homeland, or as a formerly independent people under occupation, but rather as one of China’s many “minority nationalities.” By fracturing the Tibetan homeland, the CCP sought to weaken pan-Tibetan solidarity, mask the reality of an occupied nation, and absorb Tibet into the broader Chinese national narrative as an inseparable part of China’s multi-ethnic state. It enabled Beijing to impose direct control through multiple provincial authorities while presenting to the international community a manufactured claim that “Tibet” refers only to the TAR—a fraction of the Tibetan Plateau.

Historical Map of Tibet

(Map by Tibet Action Institute)

The claim that the TAR alone constitutes Tibet is belied by the CCP’s map of Tibetan autonomous prefectures and counties that closely follows the true map of Tibet with Tibetan areas making up the majority of the current province of Qinghai, a significant portion of Sichuan, and small parts of Yunnan and Gansu. The truth of Tibet’s geography is also revealed in the facts of the Tibetan population, of which slightly less than half is in the TAR. Since the Tibetan national uprising in 2008, the CCP’s major policy meetings on Tibet have included all Tibetan areas, not just the TAR. However, their public propaganda continues to deny the reality that Tibet consists of the three provinces of Kham, Amdo, and Ü-Tsang.

Map of Tibet in Prefectures and Counties Designated by the Chinese Government

(Map by Tibet Action Institute)

Not only has China carved up the whole of Tibet with its imposed administrative divisions, traditional regions or cultural areas have also been split up with no regard for their common heritage and history. For example, the cultural area of Dege was once a kingdom in its own right with a very special history but now spans across different provinces, prefectures, and counties. According to Tibetans, Dege is part of the province of Kham. The Chinese government’s Dege, on the other hand, straddles the Tibet Autonomous Region and Sichuan Province, two prefectures (Chamdo Prefecture on the Tibet Autonomous Region side and Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture on the Sichuan side), and various counties in both prefectures. These kinds of boundaries disrupt the common bonds and ties shared by the Dege people, especially since it can be hard for Tibetans in Tibet to cross provincial borders, in particular to and from the TAR.

The CCP deliberately obfuscates what Tibet is, where CCP policies for Tibet are being applied, and who is being impacted. For example, when answering questions about the high number of Tibetan children in boarding schools at China’s review by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, a Chinese government official stated that half of students in Tibet (meaning the TAR) were boarding, and “as for the figure 1 million [children in boarding school or preschool] I don’t know where is this figure from, but I have another figure, in 2020 the Tibetan population was 3.64 million. The minority groups account for 3.2 million.” He continued, explaining that the estimate of one million was thus not accurate. He steadfastly failed to acknowledge all Tibetans living outside the TAR when his own country’s Seventh National Census of 2020 published that there were over 7 million Tibetans in total in the whole of the PRC. Approximating the total Tibetan population worldwide will be explored separately in a later update to this media resource guide.

Names and Naming

Place Names

The politics behind Tibetan language and Chinese language place names is a reflection of the broader struggle in occupied Tibet today. Tibetan place names form a collective memory often carrying deep cultural, religious, and historical significance reflecting Tibetan language, Buddhist traditions, cultural heritage, and the natural landscape. The place names in Chinese, on the other hand, reflect the administrative and political priorities and narratives of the occupying state. Understanding and foregrounding Tibetan place names and their significance is crucial in the fight against erasure.

Following China’s invasion, many Tibetan place names were written in a Sinicized version and foregrounded or changed to reflect Chinese political narratives. A good example of this is the city of Dartsedo in eastern Tibet, Kham. The Chinese name of “Dajianlu” 打箭炉 was based on the Tibetan “Dartsedo” but was replaced by “Kangding” 康定 in the early twentieth century, referring to the stabilization—or defeat—of Kham. Therefore, by Kangding becoming the most common name today, the traditional Tibetan name is being erased while the name reinforcing China’s administrative control becomes the norm.

In English language reporting, it is vital to bear in mind that the changing of place names or foregrounding the Chinese name asserts the CCP’s control while erasing Tibetan history, identity, and memory. It is more important than ever to counter these efforts by paying attention to Tibetan place names and putting these first.

Further Resources:

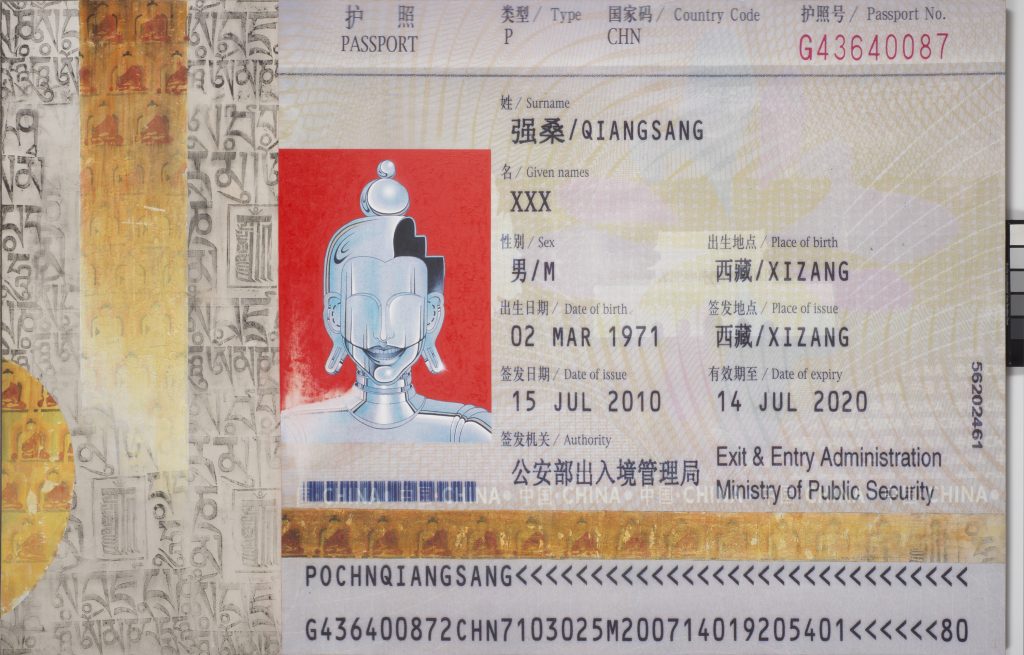

People’s Names

As with locations, when it comes to the transliteration of names, it is a political choice whether to romanize from the Chinese or the Tibetan. Given the intentional Sinicization of Tibet and Tibetan names, it is critical when transliterating to utilize the original Tibetan. Names are the cornerstone in any culture of one’s personal and cultural identity. Tibetan names are traditionally given to babies by lamas and the names are a source of cultural pride and can reflect Buddhist concepts, virtues, Tibet’s nature, and be passed down through generations. For this reason, the most common first name currently is “Tenzin” as the name comes directly from the 14th Dalai Lama, whose own name is Tenzin (Gyatso).

The majority of households do not have a common family name (the exception being older and more established aristocratic families). If a family does have a family name, it typically is placed first, e.g., Tsarong Dasang Damdul. While most Tibetans have two names, there are some who only go by one or, more commonly, by a nickname. It is also common for people with two names to shorten or contract them for convenience, so that Tsering Yangchen would become Tseyang.

Generally, people from Central Tibet have two names, each with two syllables. On the whole, they are gender neutral. In Kham and Amdo, naming practices may differ and names can be three syllables long e.g., Jamyang Kyi or Dhondup Gyal.

Tibetan names, when rendered in Latin script, can vary in spelling. As an example, the names Tashi/Trashi (Tibetan: བཀྲ་ཤིས། meaning “auspicious”) and Dickyi/Diki/Dekyi (Tibetan: བདེ་སྐྱིད། meaning “happiness”) are common and there is no standardized Tibetan phonetic transcription. In Chinese characters, Tashi is written as 扎西, which in pinyin romanization is Zhaxi. Dickyi is written as 德吉 in Chinese, which in pinyin is Deji. Therefore, whether to use Tashi or Zhaxi, Dickyi or Deji when writing in English becomes a political choice.

One further administrative challenge and headache for Tibetans from the PRC is that Tibetan names in Tibetan language aren’t officially recognized by the Chinese government. On official ID cards, names are frequently replaced with titles such as “FNU,” for “First Name Unknown,” or “XXX.”

Many Tibetans in exile have adopted the practice of family names. It is therefore culturally respectful to ascertain the preferred name to use in person and in print. It is also important to bear in mind that some Tibetans prefer to assume a pseudonym or remain anonymous for fears of repercussions when speaking to media, either for themselves or for their families. In these cases the safety and security of the individual is paramount.

Further Resources:

Language for writing about Tibet and Tibetans

The Dalai Lama’s Succession

With the Dalai Lama turning 90 on July 6, 2025, attention has been turning to the period after His Holiness and the question of his succession or reincarnation. His Holiness has affirmed in a statement made public on July 2, 2025 his intention to reincarnate and for the institution of the Dalai Lama to continue after him. For Tibetans, even though this is an emotional, sensitive, and difficult topic, it’s important that the process of succession be carried out according to His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s wishes, by the people he entrusts, according to Tibetan Buddhist tradition, and without the interference of the Chinese government, as has happened in the past.

Here are a few key points to keep in mind when interviewing Tibetans or discussing this topic:

1. The Chinese government has no say in the process of the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation

The Chinese government has actively been trying to co-opt the reincarnation system and bring it under their control. For example in 2007, the State Administration of Religious Affairs (SARA) passed Order No. 5, or “Management Measures for the Reincarnation of Living Buddhas in Tibetan Buddhism.” The order basically banned lamas from reincarnating outside the PRC and brought searching for reincarnations under government control.

In March 2025, Li Decheng, deputy director general of the “China Tibetology Research Centre” told a forum in Beijing that, “If the next Dalai Lama is declared to have been reincarnated abroad, I think it is illegal.” He further commented that the concept of a successor born outside the PRC “does not conform to religious rituals, historical customs or China’s management methods for the reincarnation of Tibetan Buddhism’s living Buddhas. He cannot be recognised.”

However, the Chinese government has no say in the process. The Dalai Lama has affirmed that he is the sole authority over any future reincarnation. Tibetans have been managing this process for half a millennium and will keep doing so.

2. The Dalai Lama has said that the movement for freedom will continue after him.

In his book Voice for the Voiceless, His Holiness clearly states that, “Since the purpose of a reincarnation is to carry on the work of the predecessor, the new Dalai Lama will be born in the free world so that the traditional mission of the Dalai Lama—that is, to be the voice for universal compassion, the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism, and the symbol of Tibet embodying the aspirations of the Tibetan people—will continue.”

Furthermore, in an op-ed in the Washington Post on March 6, 2025, His Holiness wrote: “Given that ours is a struggle of a people with a long history of distinct civilization, it will, if necessary, continue beyond my lifetime. The indomitable spirit and resilience of Tibetans, particularly inside Tibet, remain a source of inspiration and encouragement for me. The right of the Tibetan people to be the custodians of their own homeland cannot be indefinitely denied, nor can their aspiration for freedom be crushed forever.”

3. The Dalai Lama’s legacy is one of enlightened leadership and democracy.

In 2011, the Dalai Lama fully devolved political power to the Sikyong (President) of the Central Tibetan Administration (Tibetan Government in Exile) who is democratically elected. Tibetans in exile have been able to vote for their leader since 2002, while the Chinese government is now in its eighth decade of denying all people across the country the right to participate in elections. Many Tibetans see His Holiness as having given Tibetans gifts that are beyond words to describe, and his light will always shine like a beacon, leading the way towards a free future.

His Holiness has led the Tibetan people and nation in their struggle for freedom for more than seven decades, during which time he has built an incredible legacy of democracy, religious and cultural freedom, and comprehensive Tibetan-language schooling for Tibetans. He has also made a monumental contribution to the promotion of religious tolerance, compassion, and nonviolence around the globe.

Inside Tibet, students, monks, nomads, and people from all walks of life continue to assert their right to be Tibetan, even as China tries to force them to become Chinese. They celebrate their culture, their religion, and their devotion to His Holiness despite these acts being risky and outlawed. In addition, they find ways to hold on to their grasslands as authorities try to steal it, and to teach their children Tibetan language and history when the government forces them into Chinese boarding schools.

Further Reading:

- His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s Statement Affirming the Continuation of the Institution of the Dalai Lama, July 2, 2025

- His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Voice for the Voiceless, HarperCollins 2025

- International Tibet Network, May 2025, Protecting Tibetan Religious Rights: Addressing China’s Reincarnation Policies

- International Tibet Network, October 2022, Tibet, the Dalai Lama and The Geopolitics of Reincarnation

Why “Tibet” is not “Xizang”, Tibet is Tibet

The PRC’s efforts to control the language about territories under its occupation have been well documented. The Uyghur Human Rights Project has written about the importance of rejecting the colonial “Xinjiang” (Chinese meaning “new frontier”) and instead referring to the region by the names used by Uyghurs themselves: “the Uyghur homeland,” “the Uyghur Region,” and “East Turkistan.” East Turkistan is widely used among Uyghurs in the Uyghur language as “Sherqiy Türkistan.”

For decades, Chinese officials used “Tibet” in their English-language communications but towards the end of 2023, they started to increasingly use the pinyin romanization Xizang to refer to Tibet, or specifically the TAR. At academic conferences, Chinese scholars also started to use Xizang instead of Tibet in English. Most significantly, in November 2023, China published a white paper on the “Governance of Xizang,” whereas previously they had used the word Tibet when publishing reports on policy.

This change in nomenclature broadly reflected the forced assimilation drive targeting mainly Tibetans and Uyghurs under Xi Jinping, who has sought to shape one Chinese identity. Xizang, however, only refers to the TAR and does not include the traditional provinces of Amdo and Kham. In contrast, in English, Tibet does include the entirety of historical Tibet. In Tibetan, the word for Tibet is Bod བོད་ and this also implicitly refers to the entirety of historical Tibet.

As Tibetan historian Tsering Shakya notes, “China’s demand that the international community adopt “Xizang” mirrors colonial practices of renaming territories to assert dominance. By replacing local or widely recognized names with imperial ones, colonial powers erased Indigenous identities and histories. Similarly, China’s renaming effort aims to subsume Tibetan identity within a Han-centric narrative, erasing the region’s distinct cultural and historical significance and marginalizing Tibetan voices, their heritage, and their sovereignty.”

Tenzin Dorjee, in an essay co-authored by James Leibold, warns, “If the world comes to accept Xizang as the norm, then the question of Tibetan sovereignty and self-determination becomes linguistically illegible.”

When it comes to the erasure of Tibet, much writing and reporting on Tibet does not center Tibet or even say Tibet. Headlines and articles repeatedly call Tibet a “region in western China” or “China’s Tibet.” Tibet has also been euphemised as being a “Himalayan Region” or being part of the “Himalayan World,” but this is also not accurate as only a small percentage of Tibet is Himalayan. Simply saying “Tibetan Plateau” minimises Tibet to a geographical area and takes away from the idea of Tibet as a sovereign nation and its own territory, history, and unique identity.

Further Reading:

- Tibet Must Stand! by Tsering Shakya, December 11, 2024

- Beijing Wants to Erase Tibet’s Name. Don’t Let Them By Tenzin Dorjee and James Leibold, May 2025

- Tubote, Tibet, and the Power of Naming by Elliot Sperling, 2011

Why Terms Such as “Ethnic” and “Minority” Should Be Avoided

The CCP has developed its own narrative on the Chinese nation and Chinese people that is imposed from the top down. A key concept of China’s national identity as developed by the CCP is Zhonghua minzu (中华民族), often translated as “Chinese nation” or “Chinese ethnic group.” This concept attempts to unify the entire population of the PRC as one to bring about a shared cohesive identity and reinforce a political ideology.

When it comes to the term minzu (Chinese: 民族 ), it can be translated into English as minority or nationality or ethnic group. However, minzu is very particular to the CCP as the vast majority of people in the PRC are Han and make up approximately 91.1% of the population according to the 2020 census. Therefore, the CCP in the 1950s carried out a classification and made it official in 1954 that all other groups fell into 55 categories of “ethnicity,” including Tibetans.

While the word minzu in Chinese does not carry any connotations related to state or nationhood, in English, nationality does connote nation or nationhood. In order to avoid this connotation, China increasingly avoids English terms in favor of using the Chinese term minzu. An example of this can be seen in the renaming of the Central University for Nationalities as the Minzu University of China in November 2008. In official statements, reports, or educational materials, the Chinese government will often emphasize “minzu unity” and the development of various “minzu” groups.

The classification of “ethnic groups” is very much tied to the CCP’s political strategies and goals. Therefore, in order not to reinforce the CCP’s ideology, it is not necessary to write “ethnic Tibetan” or “ethnic minority,” especially as Tibetans have a rich national history and sense of nation. Referring to Tibetans as ethnic minorities reinforces the CCP’s playbook and underscoring a false and imperialistic ideology of one multi-ethnic Chinese nation state with one single Chinese national identity.

Directory of Tibetan Experts

This directory of Tibetan experts representing a variety of voices who can be contacted to speak on all Tibet-related issues. All but one are living in exile and thereby able to speak freely. The directory includes Tibetans of all ages, backgrounds, spread over different parts of the world, born in Tibet and in exile, and over half of them are women.

Recommended Reading on Tibet by Tibetans

Voice for the Voiceless: Over Seven Decades of Struggle with China for My Land and My People by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

The Dragon in the Land of Snows by Tsering Shakya

Memories of Life in Lhasa Under Chinese Rule by Tubten Khétsun

Forbidden Memory: Tibet during the Cultural Revolution by Tsering Woeser

Tibet on Fire by Tsering Woeser

The Struggle for Tibet by Wang Lixiong and Tsering Shakya

One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet by Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa

My Tibetan Childhood: When Ice Shattered Stone by Naktsang Nulo

We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies by Tsering Yangzom Lama

A Home in Tibet by Tsering Wangmo Dhompa