Tibet called ‘training ground’ for more Chinese expansion

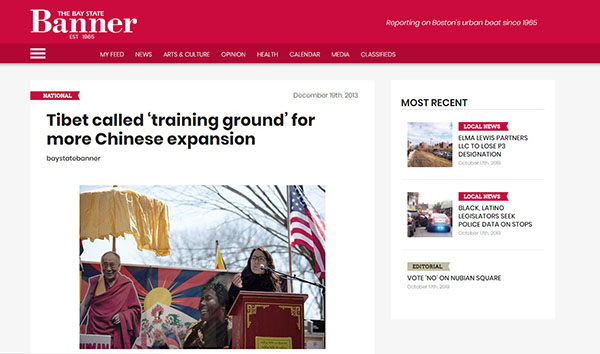

Tibetan Action Institute Director Lhadon Tethong frequently participates in demonstrations in Harvard Square with other Tibetan activists. She likens China’s actions in Tibet to its increasing expansion and harvesting of natural resources in Africa.

The Tibetan human rights activist, speaking to an audience of Harvard students, denounces the incursion of Chinese mining companies, citing their corrosive influence on the economy, the environment and the rule of law. But most of all, on the people.

“They’re simply not benefiting from the extraction interests,” says Lhadon Tethong, director of the Tibet Action Institute. “They bring in Chinese workers, tear up the land and put local enterprises out of business because they can’t compete with cheap Chinese goods flooding into the market.”

When locals do get hired, “the wages are extremely low and the working conditions are horrible. And when they complain, the local government does nothing.”

Tethong, a prominent spokeswoman for Tibetan rights, is talking about Chinese exploitation of massive zinc, copper and lead deposits in Tibet. But she could also be talking about Zambia, where Chinese-owned companies have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in copper and coal mines. Strikes by Zambian workers in the impoverished African nation have been met by brutal reprisals, forcing even the usually compliant Zambian government to take action.

According to a number of activists, China’s interests in other developing countries follow a similar pattern, all modeled on China’s 50-year domination of its small and largely agrarian Buddhist neighbor.

“When you look at China’s presence in Zambia, Peru, the Congo and other nations, it comes down to one thing and one thing only – access to resources to feed the growing Chinese economy,” says Tethong, who lives in Somerville with her husband, who was also raised in the Tibetan exile community.

“Even when some of the companies are called into account, you see them continue to act with impunity. Just like in Tibet, there is no incentive for them to act better. The state-owned companies, with deep ties to Communist Party leaders in China, are interested only in making as much money as possible with little or no respect for environmental standards, working conditions or labor rights.”

Tibet, spread across a broad plateau tucked beneath the shoulders of the Himalayas, emerged as a unified empire in the seventh century and maintained a shaky autonomy for 1,300 years. Occupied at times by Mongol and Chinese overlords, Tibet’s independence ended in 1951, when a full-scale invasion by the People’s Republic of China crushed the government. Estimates of the number of Tibetans killed since Chinese troops entered the country range from 200,000 to one million.

About six million Tibetans live in China and the Tibetan Autonomous Region, which is roughly twice the size of Texas, but at an average elevation of 13,000 feet. The provinces of the old Tibetan empire cover about one-third of China’s current land mass.

For most Americans, the beatific figure of the Dalai Lama captures the struggles of the Buddhist people for sovereignty. The 14th Dalai Lama has served as the nominal head of the government-in-exile since his escape from Lhasa’s fairyland Potala Palace in 1959.

The saffron-robed religious leader has repudiated the post-invasion government that accepted Tibet’s incorporation into China in exchange for limited autonomy. While actors and celebrities, most notably Richard Gere, have flocked to the side of the charismatic Dalai Lama, the grinding work at the grassroots level to build support for greater autonomy for Tibet has been carried out by organizations like Tethong’s.

By broadcasting the impact of China’s economic policies in the Third World, groups like the Tibet Action Institute hope to build alliances to pressure China into expanding civil liberties and human rights in Tibet.

Raised in Canada, Tethong, 37, became a widely sought commentator in the lead-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, as Chinese policies came under increased scrutiny. Passionate and well-informed arguments from the telegenic spokeswoman generated broad sympathy for Tibetans, but the media coverage resulted in little more than symbolic challenges to the powerful People’s Republic.

Linking Tibet’s struggle to Chinese expansion in Africa has also yielded limited results. China’s appetite for raw materials to feed the world’s fastest-growing economy is vast and Africa’s reception generally welcome, especially when accompanied by generous aid packages, no strings-attached loans and overbidding for equity positions in African companies.

As a result, China now receives as much as 30 percent of its oil imports from Africa, with Angola overtaking Saudi Arabia as China’s biggest supplier. China’s relations with oppressive regimes in Zimbabwe and Sudan — supplying the Harare and Khartoum governments with military hardware while striking oil and mineral deals — have drawn criticism for helping to prop up so-called pariah states.

Chinese officials insist their interests are value-neutral, deny any violation of local laws and point to the creation of hundreds of thousands of jobs and new economic activity where their companies operate. As for Tibet, China cites an historic claim to the territory dating back at least to the Qing Dynasty, when the 17th century Manchu rulers of China established a protectorate over Tibet.

Tethong, a regular visitor to college campuses and a frequent participant in weekly demonstrations in Harvard Square by Tibetan activists, dismisses such claims, pointing to unique aspects of Tibetan language and culture that clearly set them apart as a separate polity with a legitimate right to at least greater autonomy if not independence.

The rising incidence of self-immolation by nomadic Tibetans, coerced to trade the open skies and yak herds of their traditional existence for life in cement apartment blocks, symbolizes the cultural genocide now occurring in her homeland, she says.

“Over the last three years, there have been at least 122 of these acts. The story of self-immolation is the story of Chinese oppression,” says Tethong. Nomadic Tibetans, along with members of the middle class and monks, are setting themselves afire in marketplaces and at monastery gates as acts of protest, “to give their lives for a higher purpose.”

In one note left at the scene of an immolation, an impoverished herder wrote, “I am poor. I am uneducated. All I have to offer is my body.”

The resettlement activities make it easier for Chinese companies to go after some $600 billion in extractable copper discovered in the high Tibetan plain and to control the waters that rise in the Himalayas and feed the largest rivers in China and Southeast Asia, says Tethong.

“At a minimum, we need to keep the spotlight on Tibet,” she says. “This is a fight for resources that goes far beyond Tibet. If we remain vigilant, the tide will change. It’s just like South Africa. It’s a freedom struggle.”