You Spy, We Chat

Tenzin Choedak spent much of his life cut off from his family. He fled his native Tibet as a young boy in 1991 and traveled to India with his uncle, amid the growing infringement of cultural and political rights at home.

At the time, landline phones were the only available means of communication, but pricey phone calls were few and far between and out of reach for most students at his boarding school in India. In his early 20s, he was able to download the Chinese messaging service WeChat, so he could talk regularly with his family.

WeChat, a messaging service released in 2011 by the Chinese conglomerate Tencent, is the most popular social media platform among the roughly 90,000 Tibetan refugees in India. It has become a rare means of communication with people in Tibet, one of the most isolated regions in the world, where American tech companies like Facebook and Google are blocked by the Chinese government.

But now, as India and China ramp up fights over Chinese apps, a community of refugees is caught in the middle — forced to choose between surveillance and not being able to keep in touch with families.

Many in the Tibetan diaspora credit WeChat for helping them maintain relationships with their friends and relatives living on the other side of the Himalayan border.

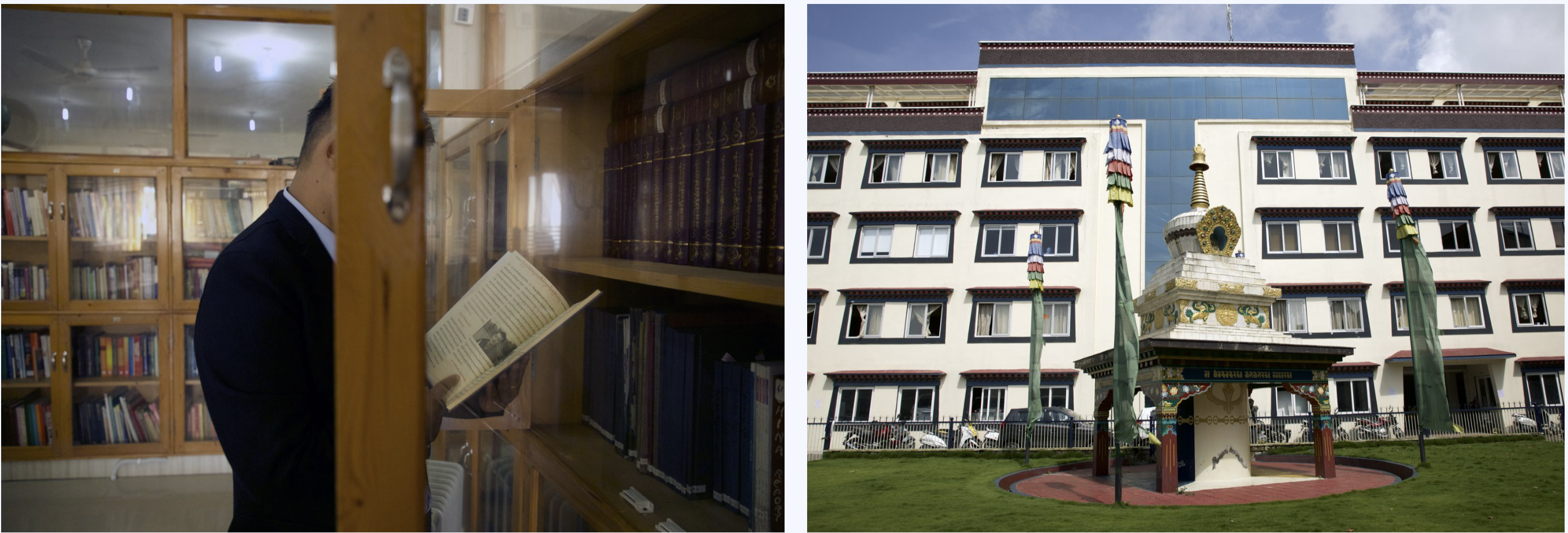

Choedak, currently a student at the College for Higher Tibetan Studies in Sarah, located in rural North India, said WeChat helped bring him closer to his family.

Like many young children in the 1990s, Choedak was sent to India to study at a Tibetan school, following the Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing. The Chinese state had imposed a renewed crackdown on religious and political activities across its territories. It was also becoming increasingly difficult for Tibetan children to complete their education in their mother tongue, as nearly all middle and high schools in the Tibetan Autonomous Region had switched to offering instruction in Chinese. This furthered the exodus of Tibetans, which began in 1959 after a failed uprising against Chinese rule forced the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibetan people, into exile in India.

Choedak says WeChat helped bring him closer to his family in Tibet.

“[Tibetan refugees] first downloaded the app, because it was the only way for them to speak with family and loved ones in Tibet,” Tenzin Dalha, a research fellow at the Tibet Policy Institute in Dharamsala, India, told Rest of World. “What has also helped fuel its wide usage among the community is that, now, most Tibetans, both inside and outside Tibet, have access to the internet.”

The extent of the app’s popularity and influence, Dalha said, was perhaps best displayed during the 2016 Tibetan general elections, when it emerged as a political campaigning tool for candidates vying for a seat in the parliament of the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), which acts as the government of Tibetans in exile, overseeing Tibetan schools and providing services to Tibetan refugees.

Tibetans around the world actively engaged in campaigning and discussions about the elections on the platform, said Dalha, even though the CTA maintains a tough stance against China, and Lobsang Sangay, the current president, has spoken out against using WeChat in the past.

In months leading up to the election, candidates and their supporters created several WeChat groups to campaign and organize discussions. The platform provided an unprecedented opportunity for a dialogue and interaction between candidates and voters, said Dalha.

But although the app has helped open up communication between those living in exile and those in Tibet, its perceived closeness to the Chinese government and its potential to be used as a surveillance tool have been causes of concern, particularly among Tibetan activists who have long been targeted with cyber attacks.

Because WeChat is based in China, it must disclose information to the Chinese government, according to that country’s cybersecurity law. This means that Tibetans communicating on the app are handing over their communications to be read and possibly censored by Chinese officials.

“It’s no secret that WeChat engages in censorship at the behest of the Chinese authorities and that it flags off accounts found to be sharing information deemed ‘controversial’,” said Lobsang Sither, digital security program director at the Tibet Action Institute, a nonprofit focused on promoting use of technology for advocacy and awareness of cybersecurity within the Tibetan diaspora community. “Therefore, Tibetans need to understand the risks associated with using the app.”

The platform actively censors accounts based in China and engages in surveillance of non-China-based accounts, according to The Citizen Lab, a research center at the University of Toronto. Some of the keywords blocked on the platform include references to the Tibetan independence movement, Free Tibet, and a Tibetan rights group, the Tibetan Youth Congress.

“Depending on what keywords you use, your entire conversation may be censored or your account may be flagged for surveillance,” said Sither.

Central Tibetan Administration acts as the government of Tibetans in exile.

Central Tibetan Administration acts as the government of Tibetans in exile.

In a 2016 Amnesty International report on user privacy, Tencent scored a zero out of 100 for failure to declare government requests for users’ personal information and for not deploying end-to-end encryption of messages. The report also notes that the company was the only one among the 11 analyzed that had failed to state “publicly that they will not grant government requests to backdoor the encryption on their messaging services.” This has privacy and safety implications for the platform’s 1.1 billion users, about 100 million of whom are based outside of China.

At least 29 Tibetans were arrested or detained in connection to their WeChat posts between 2014 and 2019, according to the Tibet Action Institute. The real number is believed to be much higher.

In July last year, a Tibetan man from the Sichuan province was detained for sharing a photo of the Dalai Lama on WeChat. He spent ten days in custody, according to a report from Radio Free Asia. More recently, there have been reports of several Tibetans being detained for sharing information related to Covid-19 on the platform.

Last December, nine Tibetans, including environmental campaigner A-Nya Sengdra, were sentenced to up to seven years in prison after being convicted of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” and “gathering people to disturb public order” by a court in Golog Prefecture in eastern Tibet. Sengdra and his co-defendants were indicted on charges related to creating two WeChat groups about local corruption and environmental protection.

In July, two Tibetan musicians were sentenced to up to seven years for dedicating a song to the Dalai Lama, which was shared on social media.

The platform has “increasingly employed artificial intelligence to scan and delete images that were deemed to include banned content,” according to a 2020 report from Freedom House, an American watchdog organization. Large-scale deletion of posts and accounts also occurred throughout 2019, according to the same report.

A man watches a live video of the Dalai Lama on his phone.

A man watches a live video of the Dalai Lama on his phone.

WeChat users interviewed for this piece said they stayed away from any political discussion on the platform and did not mention the Dalai Lama or the Tibetan independence movement. Some admitted to using code words to talk about sensitive topics.

“If I want to ask my parents about the political situation in Tibet, I say, ‘How’s the weather there?’ and if the answer is ‘not good,’ I know not to call for a couple of days,” said one user based in Dharamsala, India. “I also refer to the Dalai Lama as uncle and Chinese government officials as neighbors.”

WeChat censors content before it can reach other users through a remote server. This makes it difficult to know which keywords are blocked on the platform. For this reason, texters are forced to resort to self-censorship in order to get their communications through, said Sither, the digital security program director at Tibet Action Institute.

This has led to further difficulty for some Tibetan refugees in India. In June, India announced its decision to ban 59 mostly Chinese apps, including WeChat, citing data security and privacy concerns.

After the ban’s announcement on June 29, 2020, the apps were removed from Google’s Play store and Apple’s App Store almost immediately. Two weeks ago, all the apps stopped working altogether. According to some users in India, it has been nearly impossible to circumvent the ban by using a Virtual Private Network (VPN), as the ban seems to be based on device IDs and not just IP addresses. A VPN is only able to mask IP addresses.

The ban came after weeks of heated border disputes with China that culminated in a deadly clash near Ladakh, a Himalayan region, which left 20 Indian soldiers dead.

The ban has been met with mixed reactions in the community. Some bemoan lost connections. Others see it as an opportunity to encourage Tibetans to migrate to a non-Chinese platform, like WhatsApp, which is available in Tibet only through a VPN.

“Banning WeChat will create a huge communication barrier, as it’s the only app used by both sides,” said one young man who wanted to go by the pseudonym Karpo, fearing retaliation against his family.

But Gonpo Dhundup, the president of the Tibetan Youth Congress (TYC), which advocates for Tibetan independence, is elated. “We are extremely happy with India’s decision, and we urge all other developed nations to follow suit,” he said. “If the coronavirus pandemic has revealed anything, it’s that China cannot be trusted with information.”

The organization has been a frequent target of cyber attacks believed to be led by Chinese hackers with ties to the government. Last September, The Citizen Lab found that hackers had targeted high-profile Tibetans — including the CTA and the office of the Dalai Lama — with similar spyware used against Uighurs around the same time.

TYC is now capitalizing on the moment to reinvigorate its “Boycott Made in China” campaign that was first launched in the 1980s.

“We have been encouraging people to remove Chinese apps due to security issues, and it’s been a hard campaign, because many use WeChat to communicate with family in Tibet,” said Tenzing Jigme, the former president of TYC. “So, indirectly, the ban from the Indian government has helped our cause, as people have started taking the fact that there are consequences of using such a Chinese app more seriously.”

Choedak saved his family’s numbers before the ban.

But activists admit that the ban will be inconvenient for those with families to contact in Tibet. They point to other alternatives, including using a VPN, to get around China’s Great Firewall. Others suggest account-based software like Wire and Element (formerly Riot and Vector), encrypted apps that are not tied to individuals’ phone numbers.

With more countries joining in calls to ban Chinese apps, the experience of Tibetan refugees in India may soon be shared by others worldwide. On August 6, 2020, United States President Donald Trump signed a pair of executive orders banning WeChat and other Chinese apps within 45 days, though what exactly this will mean in practice remains unclear.

Before the ban took effect, Choedak saved his parents’ and his sister’s cell phone numbers and landline numbers. He has yet to call them, as he needs to buy a separate phone package to make international calls.

“I can still call them, but it’s not the same, because unlike WeChat, I can’t leave them messages when they aren’t available to speak or video call them for free,” he said. “Now I have to plan my calls, and there’s always going to be concerns about phones being tapped.”

Tsering D. Gurung is a journalist and communications professional based in Kathmandu.

https://restofworld.org/2020/china-surveillance-tibet-wechat/

Leave a Reply